8 February 2024

Thursday

10 AM EST / 4 PM CET

Usus, Fructus, Abusus

ALENA BETH RIEGER

Oslo School of Architecture and Design

Respondent: Adam Przywara, University of Fribourg

Abusus was everywhere in mid-twentieth-century Brussels. Buildings were falling as fast as they were going up. A most-famous victim of this “Brusselization” was Maison du Peuple (1896-1899), the Belgian Labour Party Headquarters designed by the acclaimed Belgian architect Victor Horta. In 1963, protesters responded with outrage to the planned demolition of the building. In Venice, 1964, more than 700 architects signed a petition against its destruction. In 1965, Maison du Peuple was demolished, save the main banquet hall, the cafe, and a staircase which were marked, disassembled, and stored until plans for their use could be finalized. Most plans for reconstruction never materialized. Instead, the pieces of Maison du Peuple, totalling 130 tonnes of material, disappeared to disparate locations. Remnants of Horta’s masterpiece laid dormant in the cellar of the Saint-Gilles town hall, the backyard of the Horta Museum, a cafe in the center of Antwerp, the Brussels Comic Strip Centre, and in an underground tram station at the corner of Chaussée de Waterloo and Rue du Lycée, Brussels. 70 tons of building elements were sold to a scrap dealer. Twelve truckloads were distributed to a museum and two municipalities. A number of stone and iron pieces simply sunk into the swamp-like field where they were stored. Countless elements were looted from open storage in vacant lots.

The international “ownership” of monuments was an emerging idea of the time and the Belgian public and an international congress of architects did not agree with the abusus of their treasured building. For DocTalks, I will discuss Maison du Peuple through the lens of its owners, rather than authors, to reconsider the role they played in shaping (and destroying) the architecture.

***

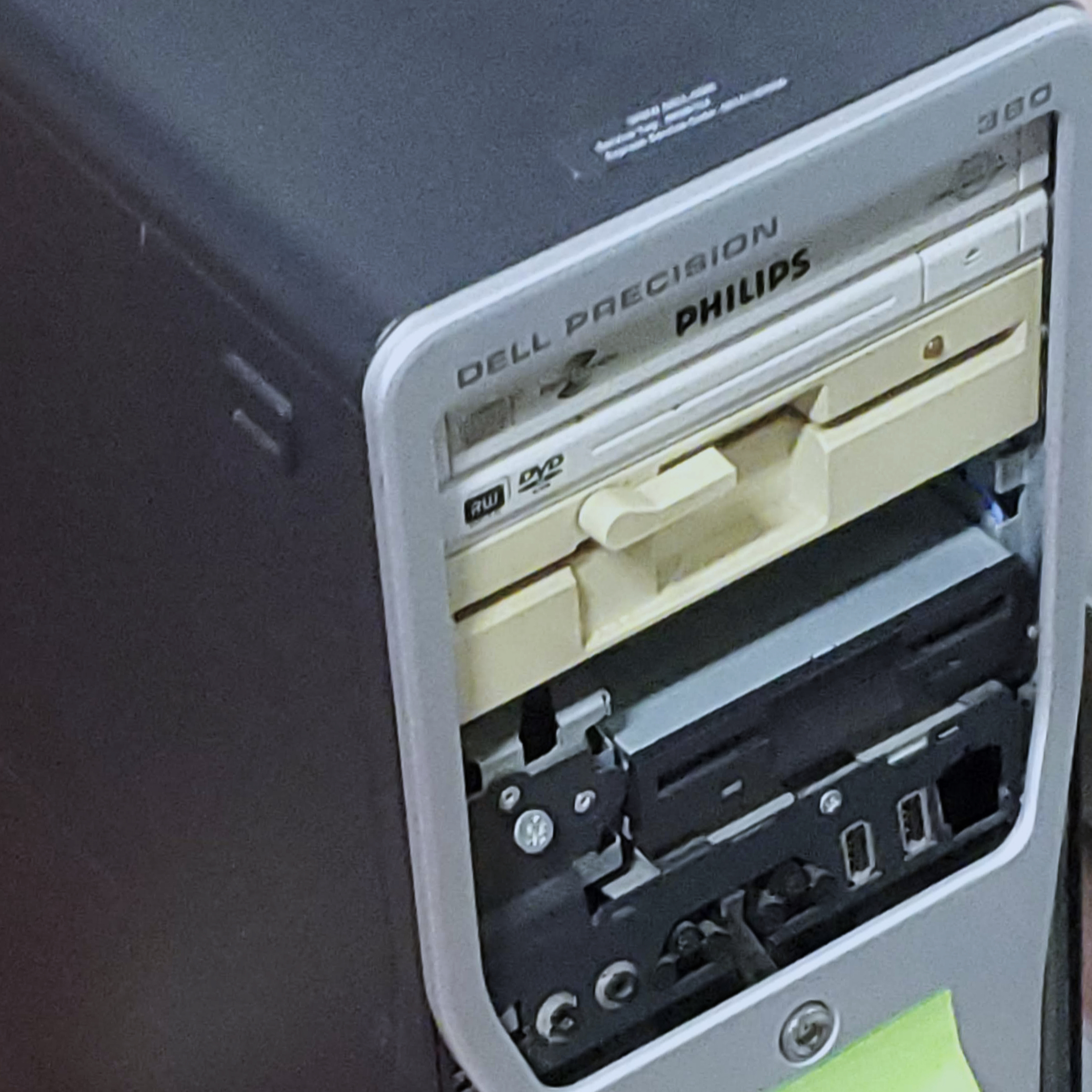

The “Frankenstein PC:” Practices of Preserving

and Erasing the Digital in Architecture

JOSHUA SILVER

The University of Manchester, Manchester Architectural Research Group (MARG)

Respondent: Eliza Pertigkiozoglou, McGill University

This paper, emerging from my current dissertation research which revisits the digital technological transformation of architectural practice since the 1980s, will discuss the pragmatics of architectural archiving through the private “living archive” of the Fondazione Renzo Piano (FRP). Simultaneously an office archive and personal-historical archive, the FRP will provide an opportunity to discuss the limits and opportunities of contemporary architectural archiving as a practice. This paper presents the technological practices of “refreshing” digital material for public dissemination through the old computing technologies collected in the “Frankenstein PC.” These practices will be discussed through the kinds of information they erase and the potential new avenues of inquiry they open.