An Inter-Institutional Platform

for PhDs, PostDocs and ECRs in

Architectural History and Theory,

Landscape and the City

for PhDs, PostDocs and ECRs in

Architectural History and Theory,

Landscape and the City

︎

Regular Talks

︎︎︎Online Sessions Link︎︎︎

︎

︎︎︎Online Sessions Link︎︎︎

10 March 2026

11:00 AM EST / 4:00 PM CET

Ashes to Ashes: Reading the Ruins of the Dutch Colonial Sugar Industry in Postcolonial Java

SANDRO ARMANDA

KU Leuven

Respondent: Javairia Shahid, Columbia University

KU Leuven

Respondent: Javairia Shahid, Columbia University

The

Wringin Anom Sugar Factory hidden behind the dense sugarcane field. Photo by

Sandro Armanda, 2025.

The Wringin Anom Sugar Factory is one of the few remaining nineteenth-century sugar factories still operating in Java today. Originally built by a British sugar manufacturer in 1845, the factory compound once functioned not only as a centre of sugar production but also as a tool of colonial control over the surrounding population and plantation landscape. Today, the site is on the verge of ruin.

Java’s colonial sugar industry began to collapse in the 1930s and was nationalised by the Indonesian state in 1958. Once a leading global exporter of sugar, Java now imports sugar on a massive scale, with Indonesia ranking among the world’s largest importers. The physical infrastructure left behind by thecolonial sugar industry – comprising roads, housing, and plantations – has largely deteriorated, yet it continues to influence rural life and labour today. For instance, the socioeconomic systems and shifts in land ownership that were established during the colonial-industrial era of the nineteenth century continue to exist. Additionally, housing facilities for sugar factory workers, built by sugar manufacturers that introduced modern construction methods, materials, and hygiene standards to the countryside, continue to influence domestic architecture in broader Javanese rural communities today.

In this presentation, I will showcase a work-in-progress paper examining the spatial, architectural, and social legacy of the Dutch colonial sugar industry in postcolonial Java through a case study of the Wringin Anom factory compound – a workers’ village designed around notions of hierarchy, efficiency, and control, which remains inhabited today. Drawing on extensive fieldwork and a lengthy research stay in the factory’s workers’ housing facilities, the paper aims to present the spatial conditions of colonial-era housing in the postcolony. It brings to light how these environments reflect and reinforce labour hierarchies, shaping the lives and livelihoods of contemporary sugar workers in Java’s rural

landscape.

***

Global Ambitions, Planetary Forces: Drainage, Urban Planning, and the Making of Iskenderun, 1851

FEYZA DALOGLU

METU, Middle East Technical University

Respondent: Sara Frikech, ETH Zurich

METU, Middle East Technical University

Respondent: Sara Frikech, ETH Zurich

Plan of the Executed Canal Project of 1851 and the Proposed

Expansion Plan for İskenderun. The National Archives (TNA), FO 195/302, no. 6.

In 1851, the third failed canal project of Iskenderun, designed to drain its centuries-old marshes, was laid out and executed by the Hungarian engineer General Maximilian Stein, who served in the Ottoman army as Ferhat Pasha after fleeing the Habsburg Empire. A former Minister of War and Governor of Transylvania, Ferhat Pasha, also prepared Iskenderun’s first urban plan. Though the canal later overflooded and the urban plan was never implemented, both projects reveal the tension between planetary processes and global pressures which would define the making of mid-19th century Iskenderun.

Iskenderun was founded on land formed by sediments carried by the sea and by streams descending from the Amanus Mountains. These geological processes produced extensive marshes and continually pushed the coastline seaward. While these planetary processes sustained a dynamic marsh ecology that actively constrained human habitation, they also created a naturally sheltered anchorage that attracted maritime interest. Fueled by expanding international trade, British efforts to establish faster communication routes to India, and Ottoman ambitions to civilize both land and population, Iskenderun was repeatedly subjected to drainage schemes under global pressure across the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and was gradually forced into being a town despite persistent environmental resistance.

This article maps out physical imprints of the 1851 canal project on Iskenderun’s land, as well as the gradual growth of the town’s built environment and its population in the 1850s. While doing so it also seeks to trace the global and empire-wide dynamics that forced Iskenderun into being.

ATTN: SESSION POSTPONED - TBA

10:00 AM EST / 4:00 PM CET

What’s Wrong with the Rural House?

On Realism and Myth in Giuseppe Pagano’s Photography

JOLANDA DEVALLE

École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL)

Respondent: Mireille Roddier, University of Michigan

Giuseppe Pagano, Haystack in the Roman Agro, 1935.

This paper reconsiders Giuseppe Pagano’s Exhibition on Rural Architecture, presented at the VI Milan Triennale in 1936, a project built around an unprecedented photographic campaign of rural dwelling across Italy, much of it shot by Pagano himself. In architectural historiography, the exhibition has long been hailed as an “anthropological inquiry,” a paradigm shift away from stylistic canons and capital-A Architecture toward humble and overlooked every-day environments. After 1945, this reading became closely bound to Pagano’s own tragic trajectory—his break from fascism in 1943, participation in the Resistance, and his death in Mauthausen in 1945. Through a redemptive lens, postwar leftist scholarship interpreted the rural exhibition as a profoundly ethical endeavor: a realist search for architecture’s collective foundations, an antidote to fascist rhetoric, an early precursor to Neorealist sensibilities. Interpretations which collectively elevated Pagano and his work as figures of critical resistance, a narrative this paper seeks to revisit and complicate.

In light of today’s renewed yearnings for the so-called vernacular and rural imaginaries, this paper approaches Pagano’s exhibition through a different and seldom discussed lens: his 1939 photographic sequence and photobook Il Covo, depicting Mussolini’s editorial office—“the lair”—the mythologized birthplace of fascism. Viewed alongside Il Covo, Pagano’s celebrated “anthropological” inquiry reveals a more ambivalent aesthetic: a double movement in which realism and myth operate simultaneously. Through a close reading of photographs, his writings in Casabella, and the catalogue Architettura rurale italiana, the paper argues that Pagano’s mode of realism isolated and abstracted fragments of the real—neutralizing class conflicts and contingency—to produce archetypal, almost mythical forms and gestures. This reframing complicates his status as precursor to postwar Neorealism and situates Pagano’s visual practice within recent philosophical reflections on fascism’s capacity to transform “reality” through myth.

In light of today’s renewed yearnings for the so-called vernacular and rural imaginaries, this paper approaches Pagano’s exhibition through a different and seldom discussed lens: his 1939 photographic sequence and photobook Il Covo, depicting Mussolini’s editorial office—“the lair”—the mythologized birthplace of fascism. Viewed alongside Il Covo, Pagano’s celebrated “anthropological” inquiry reveals a more ambivalent aesthetic: a double movement in which realism and myth operate simultaneously. Through a close reading of photographs, his writings in Casabella, and the catalogue Architettura rurale italiana, the paper argues that Pagano’s mode of realism isolated and abstracted fragments of the real—neutralizing class conflicts and contingency—to produce archetypal, almost mythical forms and gestures. This reframing complicates his status as precursor to postwar Neorealism and situates Pagano’s visual practice within recent philosophical reflections on fascism’s capacity to transform “reality” through myth.

***

The Architecture of the Making of the Author

SEVGİ TÜRKKAN

Istanbul Technical University

Respondent: Mireille Roddier, University of Michigan

The architecture of the making of the author: Tracing the pedagogy of the "loge" in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts tradition.

The late 20th century saw the intensification of attempts that expose the author as a theoretical, traditional and disciplinary construct in its complex socio-cultural entanglements. This Post-doctoral research, additionally, aims to take on a spatial perspective in the construction of the author-figure, focusing on one of the most formative chapters in the history of architectural education with continuing reverberations today.

When the seminal École des Beaux-Arts was re-established in its new complex on Rue Bonaparte in 1820, “Bâtiments des Loges” (The-Loges-Building) was the first building to be completed and used in 1824. “Loges” can be described as individual cubicles aligned on a corridor, divided by rigid walls, strictly regulated and kept under probation by guardians in order to isolate students physically and socially from the outside world and each other during the periods of architectural competitions (ranging from 2 hours to 3 months), including the prestigious Prix de Rome. Inherited from Academie Royal D’Architecture, loges were central to the pedagogy and curriculum of the École (Levine, Middleton, 1984). To counter the anonymity in the ateliers, loges assured competitors an uninterrupted space, allowing them to manifest their personal skills with a guarantee of claiming the credits in person. Although lesser published, and was abandoned after the École’s dissemination in 1968, this tiny spatio-pedagogic unit has been profound in maintaining the École des Beaux-Arts system and culture, which served as the prevalent model for institutionalized architectural education 19th century onwards.

A brief account of this lasting spatio-pedagogic tradition attempts to pin down the often-mystified production of the author in spatial lieu, revealing the socio-spatial mechanisms enabled and triggered by its architecture: the conception of creativity and isolation, the rituals of competition and surveillance, the stories of accomplishments and misbehavior.

Through a selection of drawings, postcards, administrative documents and letters from 19th and 20th century archive materials, the study will display and discuss a brief account of the “loges” as a pedagogic instrument, a cultural incubator and an authorship inscribing mechanism.

When the seminal École des Beaux-Arts was re-established in its new complex on Rue Bonaparte in 1820, “Bâtiments des Loges” (The-Loges-Building) was the first building to be completed and used in 1824. “Loges” can be described as individual cubicles aligned on a corridor, divided by rigid walls, strictly regulated and kept under probation by guardians in order to isolate students physically and socially from the outside world and each other during the periods of architectural competitions (ranging from 2 hours to 3 months), including the prestigious Prix de Rome. Inherited from Academie Royal D’Architecture, loges were central to the pedagogy and curriculum of the École (Levine, Middleton, 1984). To counter the anonymity in the ateliers, loges assured competitors an uninterrupted space, allowing them to manifest their personal skills with a guarantee of claiming the credits in person. Although lesser published, and was abandoned after the École’s dissemination in 1968, this tiny spatio-pedagogic unit has been profound in maintaining the École des Beaux-Arts system and culture, which served as the prevalent model for institutionalized architectural education 19th century onwards.

A brief account of this lasting spatio-pedagogic tradition attempts to pin down the often-mystified production of the author in spatial lieu, revealing the socio-spatial mechanisms enabled and triggered by its architecture: the conception of creativity and isolation, the rituals of competition and surveillance, the stories of accomplishments and misbehavior.

Through a selection of drawings, postcards, administrative documents and letters from 19th and 20th century archive materials, the study will display and discuss a brief account of the “loges” as a pedagogic instrument, a cultural incubator and an authorship inscribing mechanism.

24 March 2026

8:00 AM EST / 2:00 PM CET

Behind Closed Doors and Windows: Constructing the Domestic Interior in Greece,

1880–1920

THODORIS CHALVATZOGLOU

National Technical University of Athens

Respondent: Anastasia Gkoliomyti, Tokyo Gakugei University, Wenzhou-Kean University

“My Sister Penelope’s Room” Athina N. Saripolou, June 1882, watercolor,

“My Sister Penelope’s Room” Athina N. Saripolou, June 1882, watercolor, 38 × 30.5 cm. Private Collection of Athina Angelopoulou. Reproduced from Athina Saripolou-Liva: A 19th-Century Athenian Painter. Athens: Bastas–Plessas.

The scarcity of visual sources depicting urban domestic interiors in Greece from the late 19th to the early 20th century became apparent to me at the very beginning of my research. A few surviving

photographs and some scattered studies on furniture offered partial insights into spatial organization, materials, and furnishings. These allowed me to sketch a rough picture of how rooms evolved during

the period I was studying. Yet, what remained missing was a narrative—an image of how these spaces were inhabited, and by whom.

Some answers emerged with the discovery of a series of housekeeping manuals aimed at young women, at future housewives. The first, published in 1885, proved particularly revealing: such guides prescribed in detail nearly every aspect of domestic life, from cooking and hygiene to the construction and furnishing of the home. A comparative analysis of these texts provided a clearer perspective on the domestic interior, though I still had to ask to whom exactly these manuals referred. Moreover, I needed numerical data on the furniture and objects that made up an actual household of the period.

Unexpectedly, a series of legal documents—specifically dowry contracts—helped fill this gap. The dowry system, deeply embedded in Greek society, required women to bring property into marriage. The contracts I examined contained precise inventories of household furnishings, cooking utensils, and clothing allocated to brides by their families. These documents provided invaluable data for reconstructing the image of the domestic interior in which a newly married couple would live.

This paper outlines a research methodology for studying the history of the domestic interior through non-architectural texts. By drawing on disciplines such as demography, the history of emotions, and family studies, the image of what happened behind closed doors and windows becomes significantly clearer.

Some answers emerged with the discovery of a series of housekeeping manuals aimed at young women, at future housewives. The first, published in 1885, proved particularly revealing: such guides prescribed in detail nearly every aspect of domestic life, from cooking and hygiene to the construction and furnishing of the home. A comparative analysis of these texts provided a clearer perspective on the domestic interior, though I still had to ask to whom exactly these manuals referred. Moreover, I needed numerical data on the furniture and objects that made up an actual household of the period.

Unexpectedly, a series of legal documents—specifically dowry contracts—helped fill this gap. The dowry system, deeply embedded in Greek society, required women to bring property into marriage. The contracts I examined contained precise inventories of household furnishings, cooking utensils, and clothing allocated to brides by their families. These documents provided invaluable data for reconstructing the image of the domestic interior in which a newly married couple would live.

This paper outlines a research methodology for studying the history of the domestic interior through non-architectural texts. By drawing on disciplines such as demography, the history of emotions, and family studies, the image of what happened behind closed doors and windows becomes significantly clearer.

***

Small spaces of Morocco: Rooftop Terraces, Women and the Colonial Gaze

ZINAB HIMEUR

National School of Architecture Rabat

Respondent: Majdi Faleh, Nottingham Trent University

Jean Benjamin Constant – Women on rooftop terraces Tangier 1872 - Copyright Musée des Beaux Arts de Montréal (Canada)

Jean Benjamin Constant – Women on rooftop terraces Tangier 1872 - Copyright Musée des Beaux Arts de Montréal (Canada) This paper proposes a micro-historical reading of colonial Morocco through an overlooked architectural space: the rooftop terrace. Typically relegated to narrative interstices or treated as mere backdrops, rooftop terraces rarely emerge as significant spatial sites in their own right.

Building upon Swati Chattopadhyay’s work “Small Spaces: Recasting the Architecture of Empire”, this study explores how these elevated spaces were visually and culturally constructed and reconstructed, not only through urban planning and architectural form, but also within colonial literature and art, in Morocco under the French Protectorate (1912–1956).

This paper performs the archeology of these spaces, tracing how terraces mediated the encounter between colonial observers and local observed. It analyzes rooftops as thresholds between private indigenous life and the imperial gaze, where bodily visibility, modesty, and urban power relations converged. By shifting the scale from monuments to rooftops, from state plans to domestic margins, this study reveals how the Medina’s roofscape engaged in spatial politics, not only of colonial hegemony and exoticization, but also of anticolonial care and resistance.

Ultimately, this research contributes to a broader understanding of how minor spaces shaped the intimate geographies of the French colonial order, offering new ways to read colonialism, resistance and care in the architectural margins.

Building upon Swati Chattopadhyay’s work “Small Spaces: Recasting the Architecture of Empire”, this study explores how these elevated spaces were visually and culturally constructed and reconstructed, not only through urban planning and architectural form, but also within colonial literature and art, in Morocco under the French Protectorate (1912–1956).

This paper performs the archeology of these spaces, tracing how terraces mediated the encounter between colonial observers and local observed. It analyzes rooftops as thresholds between private indigenous life and the imperial gaze, where bodily visibility, modesty, and urban power relations converged. By shifting the scale from monuments to rooftops, from state plans to domestic margins, this study reveals how the Medina’s roofscape engaged in spatial politics, not only of colonial hegemony and exoticization, but also of anticolonial care and resistance.

Ultimately, this research contributes to a broader understanding of how minor spaces shaped the intimate geographies of the French colonial order, offering new ways to read colonialism, resistance and care in the architectural margins.

7 April 2026

8:00 AM EST / 2:00 PM CET

Mediating Architecture:

An Institutional Study of Knowledge Production and Dissemination at the

Canadian Centre for Architecture, 1979 - 1999

NATÁLIA CORREIA BRANDÃO

Technical University of Munich

Respondent: Masamichi Tamura, Institute of Science Tokyo

Inaugural Exhibition “Photography and Architecture: 1839–1939”, 1982. Curator: Richard Pare, CCA. Credit: Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal.

By involving wider audiences, cultural institutions such as architectural centers and museums have increasingly settled themselves as spaces for the production and dissemination of architectural knowledge beyond the academic world. In this thesis, the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA, hereafter) is analysed as a cultural institution in relation to its activities of exhibiting, publishing, collecting and researching architecture. In this direction, the archive is the common ground on which – or from which – the activities and roles to be analysed take place; it is the conductor of the communication between the interior (the discipline related professionals and activities) and exterior (the broad public). It is from the activation of the archival structure that the aforementioned domains take place, and from which they are translated into exchanges with a broader audience.

Oral history, literature review and archival research are the methodological tools in this elaboration, which are of help to elucidate the broad question of how cultural institutions dedicated to architecture produce architectural knowledge in the interface between the interior and the exterior of the discipline. Specifically, the question is hoped to be answered through the institutional analysis of the CCA, identified as one of the most relevant cultural institutions with an architectural collection, and with a gap in the literature related to its critical analysis in scientific publications. The starting point of the thesis is its act of foundation in 1979 in Montreal by architect and philanthropist Phyllis Lambert, and goes over the two decades in which she acted as founder and president.

Overall, this presentation aims to present the overall structure of the thesis, its methodology and recent findings.

Oral history, literature review and archival research are the methodological tools in this elaboration, which are of help to elucidate the broad question of how cultural institutions dedicated to architecture produce architectural knowledge in the interface between the interior and the exterior of the discipline. Specifically, the question is hoped to be answered through the institutional analysis of the CCA, identified as one of the most relevant cultural institutions with an architectural collection, and with a gap in the literature related to its critical analysis in scientific publications. The starting point of the thesis is its act of foundation in 1979 in Montreal by architect and philanthropist Phyllis Lambert, and goes over the two decades in which she acted as founder and president.

Overall, this presentation aims to present the overall structure of the thesis, its methodology and recent findings.

***

“Worlding” on Display: The Chinese Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale

(2006-2023)

YARAN ZHANG

UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER

Respondent: Alicia Lu Lin, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice

The entrance to the Chinese Pavilion at the Arsenale, photo by Yaran Zhang, 2023.

The entrance to the Chinese Pavilion at the Arsenale, photo by Yaran Zhang, 2023. Since its inaugural presentation in 2006, the Chinese Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale has

become a strategic platform for soft power projection, cultural diplomacy and national self-representation within architectural discourse. This research argues that the Chinese Pavilion offers a

valuable lens through which to understand China’s presentation of its architectural culture on the international stage. More broadly, it examines how China’s involvement in the cultural platform of the Biennale reflects an ongoing practice of “worlding”—a method defined by American anthropologist

Aihwa Ong—through which non-Western actors actively position themselves within and contribute to the global order. In this context, international exhibitions function as channels of soft intervention,

allowing China to integrate into and engage with the global cultural landscape.

Drawing on archival research, oral history, and media analysis, this research investigates the curatorial strategies, theme choices, and exhibit formats of the Chinese Pavilion between 2006 and 2023. It identifies three phases in China’s participation at the Venice Architecture Biennale: Phase I (1991-2006) relied on symbolic motifs, prioritising visibility over narrative depth; Phase II (2008-2016) marked a shift toward critical engagement with social and architectural issues; Phase III (2018-2023) reflects intensified state involvement, characterised by immersive technologies and large-scale construction displays. These curatorial changes closely align with national policies over the past three decades, including Jiang Zemin’s “Bring in and Go Global” in 1996, Hu Jintao’s “Stimulate Cultural Creativity” in 2007, and Xi Jinping’s “Tell a Good China Story” in 2013.

By examining the Chinese Pavilion within the uneven geography of national pavilions at the Giardini and Arsenale in Venice, this study reveals the Biennale’s character—part art fair, part museum, and part geopolitical tool—through which China negotiates its evolving cultural identity and projects soft power on the global stage.

Drawing on archival research, oral history, and media analysis, this research investigates the curatorial strategies, theme choices, and exhibit formats of the Chinese Pavilion between 2006 and 2023. It identifies three phases in China’s participation at the Venice Architecture Biennale: Phase I (1991-2006) relied on symbolic motifs, prioritising visibility over narrative depth; Phase II (2008-2016) marked a shift toward critical engagement with social and architectural issues; Phase III (2018-2023) reflects intensified state involvement, characterised by immersive technologies and large-scale construction displays. These curatorial changes closely align with national policies over the past three decades, including Jiang Zemin’s “Bring in and Go Global” in 1996, Hu Jintao’s “Stimulate Cultural Creativity” in 2007, and Xi Jinping’s “Tell a Good China Story” in 2013.

By examining the Chinese Pavilion within the uneven geography of national pavilions at the Giardini and Arsenale in Venice, this study reveals the Biennale’s character—part art fair, part museum, and part geopolitical tool—through which China negotiates its evolving cultural identity and projects soft power on the global stage.

21 April 2026

10:00 AM EST / 4:00 PM CET

Cultivating Urbanism

TITHI SANYAL

University of Virginia

Respondent: Jessi Quizar, University of Washington

University of Virginia

Respondent: Jessi Quizar, University of Washington

Detroit's Agro-urbanity,

Detroit, USA, 2024 (Image Source: Tithi Sanyal)

For more than 130 years, Detroit has been at the forefront of urban gardening and agricultural initiatives in the United States. While French colonists established Ribbon Farms along the Detroit River in the 1700s, modern urban agriculture in Detroit has been shaped by economic struggles, population decline, ubiquity of vacant land, and food insecurity, starting with the national economic depression of 1893–97. Today, there is widespread adoption of Agroecology- “the science, practice and movement” of conservative agriculture in the city, witnessed through the proliferation of over 2280 networked urban farms and gardens. These land-based projects are enabled by initiatives and policies like the Keep Growing Detroit’s Garden Resource Program, Urban Agricultural Ordinance (2013), and the Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund (2019), which advocate for food sovereignty, particularly within African American communities and are forming an agroecological apparatus.

This talk will discuss the forces reshaping Detroit’s identity from a post-industrial city into an Agrarian City. It will demonstrate how Actor-Network Theory can serve as a methodology to examine the history of Detroit's agroecological landscape, while also examining the motivation and agency of the actors involved in the network. It will situate Detroit’s agroecological landscape within the broader trajectory of urban agriculture, highlighting its influence on urban planning and governance since the economic depression of 1893–97. At the center of this inquiry lies the question of how actants interact and what outcomes arise from these interactions that inform urban planning, design, and governance.

This talk will discuss the forces reshaping Detroit’s identity from a post-industrial city into an Agrarian City. It will demonstrate how Actor-Network Theory can serve as a methodology to examine the history of Detroit's agroecological landscape, while also examining the motivation and agency of the actors involved in the network. It will situate Detroit’s agroecological landscape within the broader trajectory of urban agriculture, highlighting its influence on urban planning and governance since the economic depression of 1893–97. At the center of this inquiry lies the question of how actants interact and what outcomes arise from these interactions that inform urban planning, design, and governance.

***

Presence, Calibration and Failure: Spatial and Knowledge Strategies in the Co-production of Drainage Infrastructures.

ALESSIO MAZZARO

Politecnico di Torino

Respondent: Matthew Kennedy, Harvard University

Politecnico di Torino

Respondent: Matthew Kennedy, Harvard University

Workshop of Radionovela, July 2025, Colonia Culturas de Mexico.

The peripheries of Sao Paulo and Mexico City are territories where the alterations of water bodies, urban development, and the conflict between opposing interests and visions are so strong it may be impossible to conceive of a definitive solution to the problems related to water. Drawing on fieldwork experience and participatory art activities with inhabitants in two different case studies, this contribution examines the dynamics of co-producing knowledge and infrastructures through the categories of failure, presence, and calibration. The territory is approached as a stage where, in response to water management challenges, actions are rehearsed and revised—together with the public—by observing and learning from their effects.

In Torresmo (BZ), an informal settlement divided by a stream whose channelization increased the incidence of flooding, failure (of a drainage infrastructure, of state technicians and of a university laboratory) generates knowledge and materializes the forces at play in the territory. Here, through a list of doubts and questions (triggered by artistic activities) about a future lamination basin, residents engage with the Secretariat of Infrastructure (SIURB), contributing to exerting pressure and to voicing alternative ways of managing water in the territory.

In Colonia Culturas de México (MX), a settlement at the edge of the former Lake Chalco, a local collective dealing with the construction of a new wastewater pipe, participates in the making of the infrastructure: being present (Taylor 2020) with their bodies and questions in the construction site and conducting a practical inquiry (Dewey 1938). Monitoring in a Whatsapp group, water level and issues in the infrastructure elements, they participate in the calibration of the drainage infrastructure. Here, calibration, that is usually a technical/engineering procedure oriented toward a predetermined outcome, becomes epistemic and a collective process of relational adjustment (Latour 2005) among heterogeneous actors (engineers, inhabitants, infrastructural elements).

In Torresmo (BZ), an informal settlement divided by a stream whose channelization increased the incidence of flooding, failure (of a drainage infrastructure, of state technicians and of a university laboratory) generates knowledge and materializes the forces at play in the territory. Here, through a list of doubts and questions (triggered by artistic activities) about a future lamination basin, residents engage with the Secretariat of Infrastructure (SIURB), contributing to exerting pressure and to voicing alternative ways of managing water in the territory.

In Colonia Culturas de México (MX), a settlement at the edge of the former Lake Chalco, a local collective dealing with the construction of a new wastewater pipe, participates in the making of the infrastructure: being present (Taylor 2020) with their bodies and questions in the construction site and conducting a practical inquiry (Dewey 1938). Monitoring in a Whatsapp group, water level and issues in the infrastructure elements, they participate in the calibration of the drainage infrastructure. Here, calibration, that is usually a technical/engineering procedure oriented toward a predetermined outcome, becomes epistemic and a collective process of relational adjustment (Latour 2005) among heterogeneous actors (engineers, inhabitants, infrastructural elements).

5 May 2026

10:00 AM EST / 4:00 PM CET

Unsettling the Typology:

Mappila Muslim Women’s Reimaginings of Gendered Domestic Space

(Kerala, India)

AKMA NAZAR

University of Westminster

Respondent: TBA

University of Westminster

Respondent: TBA

Routine scene in a Mappila home (author’s house) - the father casually occupies the veranda, while the mother cautiously retreats behind a wall, negotiating privacy and visibility from the street beyond - a subtle demonstration of tensions and conflicts between gender and space.

This research examines how gender is embedded in the contemporary (1980s-present) domestic typology of Mappila Muslim homes in Malabar, Kerala, focusing on the production and negotiation of domestic space through women’s perspectives. Architectural historiography on the Mappila community has overwhelmingly privileged the sacred or monumental (particularly mosque architecture) while leaving the architectures of everyday life underexplored. Where domesticity is addressed, scholarship has tended to emphasise traditional aristocratic residences, overlooking proletarian and contemporary homes that constitute the majority experience. This neglect reflects a broader tendency in architectural discourse to privilege the public realm over the private, rendering ordinary domestic environments analytically marginal.

My project responds to this gap by exploring how Mappila women, particularly homemakers, tactically and subversively exercise spatial agency within contemporary homes shaped by Islamic design principles, regional syncretic spatial practices and modernist architectural ideals. It unpacks ways in which these domestic spaces respond, or fail to respond, to women’s personal, social, cultural, spiritual, and religious needs.

Methodologically, the project adopts a relational autoethnographic approach combining family research and ‘friendship as method’, using spatial analysis guided by oral histories from women in my family and personal network as critical entry points into wider architectural questions. By foregrounding orality as an architectural research method, it challenges masculinist narratives of the ‘home as haven’ and instead situates women as active repositories of architectural knowledge. A feminist psychoanalytic lens enables me to map women’s affective and spatial desires, thei negotiations of domestic spaces/boundaries, and the ‘leftover’ or unarticulated dimensions of dwelling absent from typological discourse.

Through one case study, my presentation will demonstrate the gendered spatia framework of these homes (authorship, spatial layout and use, homemaking practices, etc.) and how Mappila women, through everyday practices and performances, interrupt and reimagine their prevailing domestic typology. In doing so, it reconceptualises domestic typology not as a static cultural form, but as a contested terrain of spatial agency, contributing to broader debates in architectura historiography and feminist spatial theory.

My project responds to this gap by exploring how Mappila women, particularly homemakers, tactically and subversively exercise spatial agency within contemporary homes shaped by Islamic design principles, regional syncretic spatial practices and modernist architectural ideals. It unpacks ways in which these domestic spaces respond, or fail to respond, to women’s personal, social, cultural, spiritual, and religious needs.

Methodologically, the project adopts a relational autoethnographic approach combining family research and ‘friendship as method’, using spatial analysis guided by oral histories from women in my family and personal network as critical entry points into wider architectural questions. By foregrounding orality as an architectural research method, it challenges masculinist narratives of the ‘home as haven’ and instead situates women as active repositories of architectural knowledge. A feminist psychoanalytic lens enables me to map women’s affective and spatial desires, thei negotiations of domestic spaces/boundaries, and the ‘leftover’ or unarticulated dimensions of dwelling absent from typological discourse.

Through one case study, my presentation will demonstrate the gendered spatia framework of these homes (authorship, spatial layout and use, homemaking practices, etc.) and how Mappila women, through everyday practices and performances, interrupt and reimagine their prevailing domestic typology. In doing so, it reconceptualises domestic typology not as a static cultural form, but as a contested terrain of spatial agency, contributing to broader debates in architectura historiography and feminist spatial theory.

***

Swiss Safe Space Imaginaries: archetypes of security, stability and abundance

KHENSANI JURCZOK-DE KLERK

ETH Zürich

Respondent: TBA

ETH Zürich

Respondent: TBA

former Swiss artillery fortress Sasso da Pigna at the St. Gotthard mountain pass, which was built during World War II. (Arnd Wiegmann/Reuters)

This presentation interrogates how “safe space” is (mis)translated in Switzerland, where imaginaries of safety are framed by archetypes of security, stability, and abundance. Emerging from social movements and later absorbed into broader cultural discourse, the term safe space has been widely mobilised yet rarely examined through the lens of architectural history. Within the Swiss context, imaginaries of safety manifest spatially in emblematic forms: the alpine mountain as fortress, the bunker carved into rock as guarantor of neutrality, the nuclear family as domestic stabiliser, and the bank vault—ironically called a “safe”—as the ultimate emblem of abundance. Together, these archetypes sustain a postcard image of national order and prosperity while delimiting alternative, culturally situated understandings of safety in an increasingly diverse society.

Yet these same archetypes are deeply entangled with colonial and capitalist histories: the storage of Nazi gold in Swiss banks during World War II; the financial entanglements with apartheid-era extraction economies in South Africa that underwrote Swiss domestic stability in the 1970s; and the reliance on seasonally restricted Italian migrant labour to construct the very infrastructures of safety during the late nineteenth century. These converging histories expose how Swiss safe space imaginaries both idealise national stability and simultaneously suppress other modes of being, belonging, and spatial imagination.

This presentation considers how these inherited imaginaries produce a paradoxical condition: safety as an anchored ideal built upon histories of exclusion, and yet, for many, a continually unstable and floating experience. By reading these archetypes against Black feminist articulations of safe space from the 1980s-2000s, it argues for an intersectional and socio-spatial understanding of safety that recognises and unsettles the structural exclusions on which Swiss stability has historically depended.

Yet these same archetypes are deeply entangled with colonial and capitalist histories: the storage of Nazi gold in Swiss banks during World War II; the financial entanglements with apartheid-era extraction economies in South Africa that underwrote Swiss domestic stability in the 1970s; and the reliance on seasonally restricted Italian migrant labour to construct the very infrastructures of safety during the late nineteenth century. These converging histories expose how Swiss safe space imaginaries both idealise national stability and simultaneously suppress other modes of being, belonging, and spatial imagination.

This presentation considers how these inherited imaginaries produce a paradoxical condition: safety as an anchored ideal built upon histories of exclusion, and yet, for many, a continually unstable and floating experience. By reading these archetypes against Black feminist articulations of safe space from the 1980s-2000s, it argues for an intersectional and socio-spatial understanding of safety that recognises and unsettles the structural exclusions on which Swiss stability has historically depended.

19 May 2026

8:00 AM EST / 2:00 PM CET

Architectures of Anticipation: Illustrated with Three Acts from Wartime Turkey

ELIF KAYMAZ

Middle East Technical University

Respondent: Pinar Sezginalp, Bilkent University

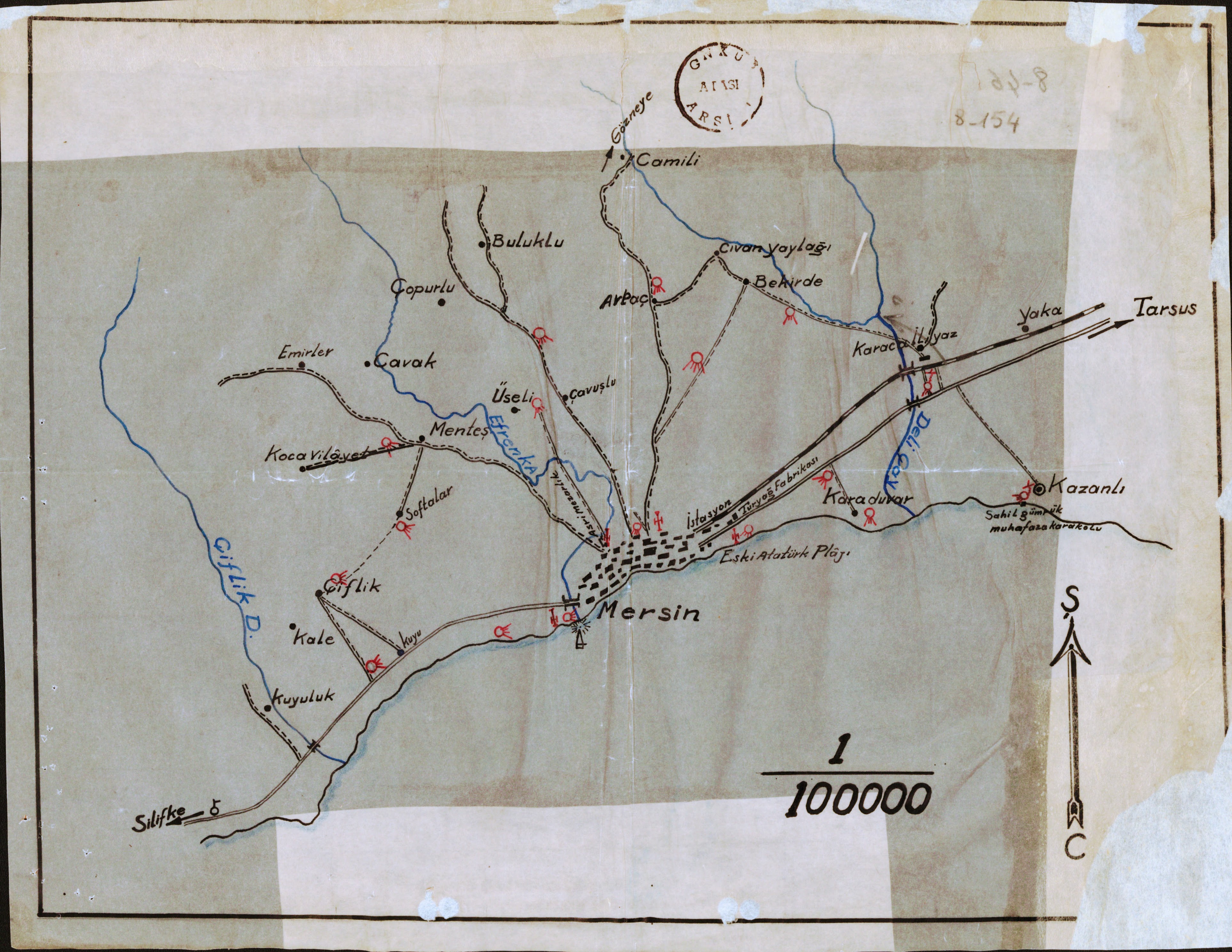

Marked with projected defensive sites, the 1:100,000 map of Mersin and its surroundings, 1941. ATASE Military History Archives, 110-9-1-14 (4/0/113)

Architectures of anticipation names how Turkey, officially neutral yet deeply entangled in the Second World War, reshaped its environments between 1935 and 1945. The expectation of conflict generated infrastructures, standards, and surveys, and redistributed responsibilities across institutions, experts, and publics. This future-oriented mindset materialized in ports and trenches, in manuals and gas-mask drills, and in the atmospheres and vulnerabilities of cities. The talk examines three acts through which this orientation becomes visible. In the south, army sergeant Vecihi Akın’s twenty-one-day field notes and sketches, produced while translating for a visiting British general, capture the routines of coastal defense under neutrality. Moving from decisions on defending hills to the social rhythms of travel, his records reveal intertwined practices of territorial assessment, diplomacy, and Allied information-gathering. In Istanbul, journalist Nusret Sefa Coşkun’s series on the Byzantine cisterns revisited the city’s underground at a time when shelter construction stalled and finances were strained. His reports on damp vaults, blocked passages, and unexpected capacities reframed these spaces as practical assets, turning the subterranean past into a prospective infrastructure of protection later echoed by foreign experts and municipal decisions. At the Red Crescent’s gas-mask factory, chemist Nuri Refet Korur’s manuals, journal writings, and experiments chart preparation at the scale of the body. The factory’s respirator production, largely undertaken by women workers, paired with Korur’s technical work to form a laboratory of design, discipline, and care, shaping new domestic expertise around toxicity and protection. These acts show how futures of destruction were made workable in the present: by mobilizing bureaucracies, furnishing environments, and inscribing routines onto bodies. They reveal communicative, territorial, organizational, and epistemological practices through which environments became governable under crisis, authority and labor shifted, and fear and hope informed spatial imagination. This framework clarifies how projected futures of war, climate, or displacement, reorder the present and why such dynamics matter for architectural history.

***

From Fences to Statutes: Privacy, Property, and Self-Governance in Post-Detonation Los Alamos, 1955-1965

LEALLA SOLOMON

Princeton University

Respondent: Heather Jahrling, Princeton University

Histories of American domesticity regard privacy as a building’s relationship to the exterior. Discourses of model suburban living have elevated Levittown as the postwar model of American living, effectively marking privacy through the typology of the suburban house and its appurtenances. The fence, lawn, shaded windows, curtains, and acoustic measures have established themselves as markers of privacy in modernity, equating privacy with the ability to separate the individual from the adjacent exterior. This presentation seeks to challenge the canonical presumption by interrogating the urban planning of Los Alamos—the infamous atomic energy town—after the detonation. It contends that under the mantle of “disposal plans” ( the Atomic Energy Commission’s federal plan to privatize Manhattan Project towns and transform them into self-governed entities), the Atomic Energy Commission reinvented American privacy and individuality. Through an extensive archival investigation of reports, studies, recommendations, official letters, and community registers produced between 1955 and 1965 in the attempt to safeguard and promote domestic nuclear production through the creation of the town’s “self-governance,” I mobilize the notion of the private from the realms of domestic design to urban planning, management, and assertion of control. In this presentation, I will show how previous privacy-generating entities, rooted in domestic architectural settings, morphed into a legal and economic mechanism that prioritized administrative and interiorized separation from the one exhibited to the outside. With an emphasis on property deeds and transfers, the ability to separate shared utilities and mortgage payments (both between families and between citizen entities and the federal government), and the simple legal definition transfer of a typology (from “multi-family house” to “single family house”), this presentation seeks to mobilize architectural privacy into the realms of law, governance, and politics. Reconfiguring privacy’s material assumptions, I challenge how privacy is thought of, conceived, practiced, and performed in the postwar world.