10 February 2026

10:00 AM EST / 4:00 PM CET

“If One Knew Where to Look:” Encoding Plants into Data at the American Horticultural Society’s Plant Records Center

SONIA SOBRINO RALSTON

Harvard University

Respondent: Camila Medina Novoa, ETHZ

The Plant Data Sciences Center's (formerly Plant Records Center) master inventory of plants in participating collections as microfiche, 1979. Arnold Arboretum Archives, photo by Sonia Sobrino Ralston.

In the late 1960s, botanical gardens and arboreta transformed from living collections to computerized databases. Influenced by the introduction of mainframe computers to research institutions and universities, the American Horticultural Society’s Plant Records Center attempted to centralize botanical accession records in collectionss nation-wide database to facilitate locating and comparing records. As AHS director Robert MacDonald wrote advocating for its development in 1973: “...a specimen of almost any cultivated plant might be found in one or more of these collections, if one knew where to look.”1Since the inception of living collections, cataloging has been a longstanding conundrum: plants defy control. As living, sessile organisms, plants’ growth and death is unfixed and monitoring requires the intense, scrutinous labor of ground truthing. From ledger to punch card, the work of horticulturalists and landscape architects to shape and maintain spaces of botanical information was complemented by a new landscape worker in the 1960s: the computer operator.

This paper explores how the mission to centralize living plant records into standardized bioinformatic system was shaped in equal measure by the limitations of early computers and the local, situated knowledge of landscape workers. Not only were plant records maintained by gardeners, laid out by landscape architects, and managed by botanical scientists, but they were also translated into accession punch cards by that were subject to the local and personal idiosyncrasies of landscape data managers. Taking a microfiche from 1979 documenting the entirety of the plant holdings of the Plant Records Center’s participating network of living collections as the starting point, this paper aims to discuss the format of the plant accession record and its translation from analog to digital format in a moment of rapid technological change. Focusing on the archival collections of the Arnold Arboretum, a main participant in the early pilot projects of the Plant Record Center, I aim to unravel the tensions between the media of encoding, the unruly plant subject, and the labor of centralization that ultimately led to the failure of a centralized national system by 1985. The paper argues that the translation to digital formats, or the microfiche, resulted in new forms of landscape labor and knowledge production, but also flattening and omissions resulting from fit fixed-length fields on punch cards. This moment of digitizing living collections thus reveals how translations from local to centralized, physical to digital, and plant to data, was not just a question of media, but one that had enduring effects on the way landscapes are known, designed, and produced.

***

THE CEMETERY AND THE

DIGITALISATION OF MEMORY: Death, collective memory and virtual space

in the contemporary city

STEFANIA RASILE

ETH Zürich

Respondent: Gruia Badescu, University of Konstanz

Frame from Ingmar Bergman’s film The Seventh Seal (1957).

The advancement of information technologies, the transition from the mechanical-analogue era to the digital age, has transformed the way we communicate and store the memory of the deceased. Carved stone, photography, hard drive, cloud storage: this sequence manifests the physical contraction of the memory container while increasing the amount of information, which apparently sheds its physical presence. Today, the production, accumulation, and daily reproduction of personal digital data impact the post-mortem dimension of individuals. The use of digital technology is conditioning the approach to memory not only from a cultural perspective but also from an architectural and urban viewpoint. The architecture of death relates to the invisible and symbolically represents the deceased through material means, aiming to endure over time and perpetuate their memory within the community despite their absence. In an era where commemorative practices are increasingly virtualized, this research explores how the digitization of memory conditions the architecture of remembrance. As its methodology, the research takes on a combination of historical analysis and digital experimentation. The convergence of these phases and approaches seeks to deepen the understanding of the monumental condition in contemporary society, viewed through the lenses of architectural history and technological development. The utilization of artificial intelligence and extended reality advances research by enabling interactive engagement, thereby bridging the physical and virtual worlds. This research tackles the architectural dimension of current sociological studies on Digital Death, exploring the intersections of collective memory, architecture, and virtual space.

27 January 2026

10:00 AM EST / 4:00 PM CET

Constructing Freedom: Slavery, Religion, and Abolitionist Architecture in the Nineteenth-Century South

HAMPTON SMITH

MIT

Respondent: Sonali Dhanpal, Columbia University

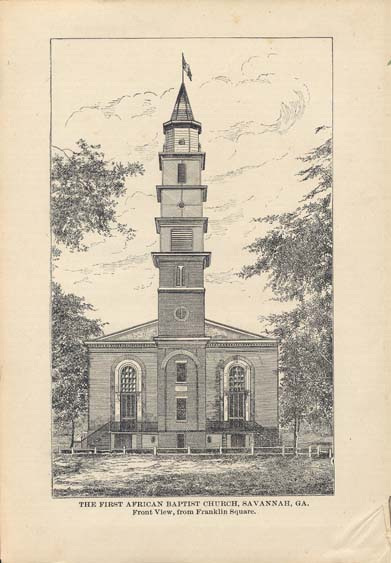

The First African Baptist Church, Savannah, Georgia, Front View, from Franklin Square. Rev. E. K. Love, D. D. History of the First African Baptist Church, Savannah, Ga. The Morning News Print. 1888.

In 1793, congregants of the First African Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia purchased land and began constructing a sanctuary with bricks fired on nearby plantations. The sixty-six years it took to complete the building marked the difficulty of sustaining a “for-us, by-us” institution under slavery, where Black worship was legally supervised and often violently disrupted. Securing a site, materials, and labor outside enslavers’ channels posed further barriers. Under these constraints, the church’s 1859 brick exterior adopted Euro-American proportions legible to officials—a tactical sign of civic legitimacy. Yet behind this façade, the story of its construction reveals underground practices of fundraising, exchange, and labor that contested planter control and cultivated Black autonomy.

First, fundraising drew on the wages of hired-out artisans, surpluses from subsistence gardening,and mutual aid networks. Second, sourcing materials avoided dependence on planter wealth and supply chains. Congregants turned instead to Savannah’s internal market, where enslaved laborers sold goods, sometimes stolen from plantations. Court records from the 1820s allege that members of the First African Baptist Church purchased bricks from enslaved brickmakers at the Hermitage, Savannah’s largest brickmaking plantation, who had taken them “without ticket with permission to trade.” These exchanges implicated the congregation directly in an underground economy that defied planter control and sustained Black community building. Third, the collaborative building process—men and women hewing timber, laying brick, and raising the sanctuary—forged reciprocal social and ecological relationships.

The sanctuary’s later role on the Underground Railroad makes clear that abolition was not only imagined but enacted in the making of the church itself. What authorities read as a brick façade of civic conformity was in fact the material record of an abolitionist practice, carried out in the very process of construction.

***

Prince Hall Freemasonry and the Construction of Black Counterpublic Space

TRISTAN WHALEN

Brown University

Respondent: Sonali Dhanpal, Columbia University

Prince Hall Grand Lodge, 1630 Fourth Avenue North, Birmingham, AL (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

This paper argues that Prince Hall Freemasonry—the Black Masonic tradition established in late eighteenth-century Boston—offers a critical lens for examining how architecture has mediated race and human difference in American civic history. Working between two temporally disparate but thematically twinned case studies, I track the dialecticalforces shaping the social and architectural production of Black counterpublic space.

In 1775, after being denied entry to Boston’s St. John's Lodge, Prince Hall (c. 1735–1807) and fourteen other free Black men were initiated into Freemasonry by members of an Irish military lodge, forming African Lodge No. 1.Meeting in Hall's leather tannery near Faneuil Hall, the Lodge became an epicenter of political activism and intellectual life, functioning simultaneously as a secret fraternal society and a forum for civic engagement. Through public charges and petitions, Hall and his colleagues strategically rewrote Masonic genealogy to position Black Americans as the true inheritors of ancient stonemasons' esoteric knowledge, forming an institution both embedded within and positionedoutside the hegemonic social order of late eighteenth-century Boston.

The layered functions of African Lodge No. 1 were later architecturally reinscribed in Alabama's Prince Hall Grand Lodge, a seven-story Renaissance Revival monolith in Birmingham's historic 4th Avenue District, completed in 1924. Designed by Robert R. Taylor, the first accredited Black architect in the United States, the temple provided essential civic infrastructure for Birmingham's Black community of over 75,000, housing the first public lending library open to Black citizens in Birmingham, offices for Black-owned businesses, and a 2,000-seat auditorium. In the 1950s and 1960s, the building became instrumental to the Civil Rights Movement, serving as headquarters for Alabama's NAACP chapter, a staging ground for protests and sit-ins, and a makeshift infirmary during the Birmingham Campaign riots of 1963.

Taking seriously Joseph A. Walkes' claim that "the history of Prince Hall Freemasonry is in reality the history of the Black experience in America," this paper examines how Prince Hall and Robert Taylor—designers of the fraternity’s civic and architectural character, respectively—negotiated the tension between public Blackness and secret brotherhood, between race as social signifier and privately felt experience, and between "traditional" Masonic historyand the reinscription of a distinctly Black Masonic genealogy.

13 January 2025

10:00 AM EST / 4:00 PM CET

Red Clocks and the Modern Metropolis: the Politics of Time in Red Vienna’s Municipal Housing Programme

JEROME BECKER

KU Leuven

Respondent: Andreas Kalpakci, ETH Zurich

Bildertafel des Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseums für die Ausstellung "Wien und die Wiener" 1927, (Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, B-72974, https://resolver.obvsg.at/urn:nbn:at:AT-WBR-132804 / Public Domain Mark 1.0).

Since the onset of modern urbanisation, significant shifts in the synchronisation of living and working have challenged daily rhythms and temporal patterns of inhabiting cities. These temporal shifts, however, have not evolved without conflict. Until today, time is perceived as a contested resource—whether in struggles against exploitative working hours, in demands for more free time, or in resistance to the gendered and racial division of labour. It strangely belongs to us, yet we have to give it away and trade it, by spending it on others or selling it as working hours. How we use and experience time is not simply a matter of individual choice but a question of social justice. It is always conditioned by how everyday life is organised—politically, economically, and spatially.

This paper examines the reciprocal relationship between the socio-political coordination of urban life and the spatial conditions in which multiple temporalities unfold, focusing on the politics of time within Red Vienna’s municipal housing programme (1919–1934). This historical case stands out as a rare instance in which time was explicitly understood as a matter of political negotiation. Drawing on archival research, policy documents, and discourse ana- lysis, I trace how the Austromarxist movement’s diverse conceptions of time—abstract, projective, and relational— shaped the spatial parameters of the housing programme.

By re-examining this well-studied case through a chro- nopolitical lens, the paper highlights an underexplored dimension of urban politics in Red Vienna and, more broadly, seeks to enrich architectural history and theory by foregrounding the temporal politics of public housing.

***

Claims from the Margins: Group Activism in Vienna’s Built Environment, 1870–1942

ULLI UNTERWEGER

University of Texas at Austin

Respondent: Elana Shapira, Universität Wien

Postcard of the Czech School Association Komenský, Featuring the Community’s First School Building. A. Werner, Around 1900 (Author’s Research Collection)

My dissertation examines how Vienna’s three largest marginalized groups—Jews, Czechs, and womenacross class lines—created spaces for themselves in the shifting socio-political landscape of the late Habsburg Empire through the Interwar Period.

Vienna has long held a central place in the canon of Western architectural and cultural history, often framed through top-down initiatives such as the Ringstraße or Red Vienna and the work of individual architects and theorists. Recent scholarship has broadened this picture by highlighting the contributions of women and Jews. Still, these accounts usually focus on professional designers or affluent clients,whereas the experiences of other marginalized groups remain largely absent. My dissertation explores these lesser-known histories by considering the activities of associations (Vereine)—democratically structured organizations that legally belonged to the private sphere but often fulfilled socio-political functions associated with the public realm.

Through five case studies—synagogue associations, a Czech school association, bourgeois women’s clubs, sports clubs, and associations of working-class women—I examine a spectrum of engagements with the built environment, from informal spatial practices to design projects by renowned architects. Three guiding questions shape my research: What strategies did these groups use to establish and maintain spaces for themselves? What role did architecture and design play in their endeavors? And how did architectural professionals—architects, designers, builders—participate in these efforts? My analysis draws on a wide range of sources, including surviving buildings, architectural plans and drawings, historical photographs and postcards, contemporary publications, and materials from private archives.

This paper discusses the methodological challenges and preliminary findings of this approach. By concentrating on associations—entities with stable legal frameworks yet shifting memberships acrossseven decades—it reflects on the possibilities and limitations of writing architectural history from acollective perspective rather than focusing on individuals.