PAST TALKS 2022

13 September 2022

Diaspora Kibbutzim:

Redefining the Zionist Settlement Movement as an Expanding and Transnational Spatial Network

REUT YARNITSKY

UPenn Architecture

Respondent: Stephanie Savio, EPFL

Inauguration of the new house of the Klosova kibbutz, January 1927.

The Ghetto Fighters’ House Archive (Kibbutz Lohamei Hageta’ot)

The Ghetto Fighters’ House Archive (Kibbutz Lohamei Hageta’ot)

The communal settlement of the Kibbutz has been extensively studied by architectural historians as the central expression of the Zionist settlement movement. However, while focused on the role of the kibbutz in the realization of Jewish nationalism in Palestine; scholars have overlooked the concurrent phenomenon of the diaspora kibbutzim, which emerged in Eastern-Europe during the interwar period. By exploring this phenomenon, I wish to expand, both geographically and thematically, the current discourse on the kibbutz, revealing a spatial organization significantly more radical and fluid than previously conceived. Dismayed by the renewed anti-Semitic sentiments, and growing political and economic instability of the 1920th, many young Jews in Eastern-Europe were seeking an outlet in Zionist activity. The Diaspora kibbutzim emerged out of spontaneous gathering of communes, who were inspired by the settlement movement in Palestine, specifically the kibbutz. However, while the establishment of the kibbutz in Palestine relied on mechanisms of landownership and colonialization, the settling system of the diaspora kibbutzim was based on an adaptation to existing built environments and communities. Each commune found local accommodation and workplaces in its hometown or nearby village, dispersing the kibbutz across different houses, apartments, rooms, and warehouses. This spatial adaptability extended beyond the single town, as the kibbutzim were constantly expending into different locations, creating flexible networks of communes throughout today’s Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus. Spatial practices such as multipurpose use of spaces and inventive methods of communication between dispersed locations, supported this mechanism. Consequently, unlike the closed institutionalized kibbutz in Palestine, the diaspora kibbutz functioned as an open non-hierarchical community, integrated and influenced by its surrounding society. I believe that retrieving this phenomenon back into the discourse concerning the kibbutz, allows to challenge its assumptions concerning colonialization, settlement, and nationalism, redefining the kibbutz as a diverse, expanding and transnational movement.

***

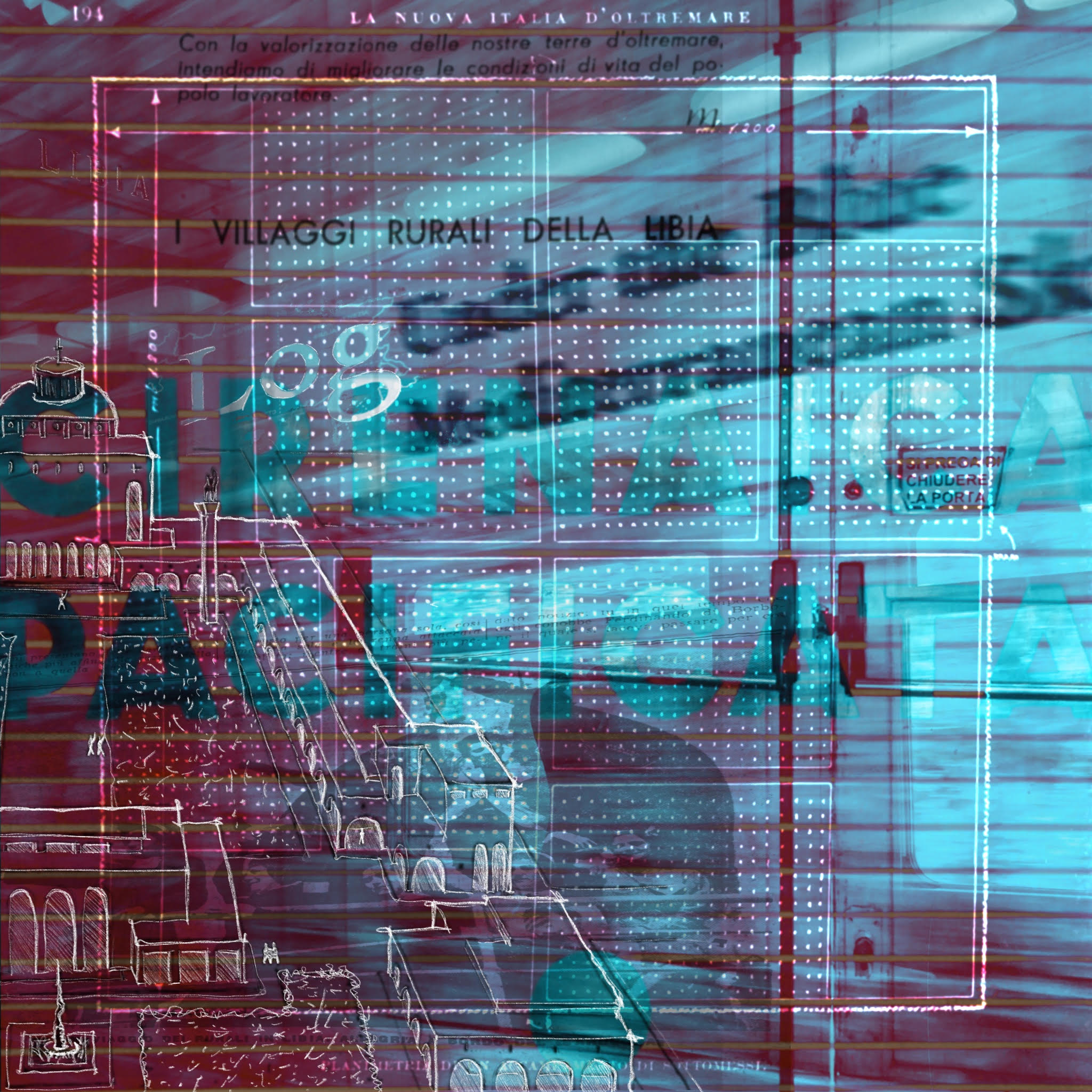

Urban-Rural Modernization of Italian-Colonial Libya: Thoughts from the ‘Sack of Civility’ and the ‘Barbaric Transmission of [Design] Culture’ [Now]

AMALIE ELFALLAH

Politecnico di Milano + Fulbright

Respondent: Lahbib El Moumni, ETH/gta

'Navigating the Italian colonial/post-colonial of Libya in Italy' a memory recalling spaces+publications (2021-2022)…the exit doors of the vestibule within the '"permanently closed" ex-colonial 'Istituto agronomico per l'oltremare' (IAO) hold a sign above the emergency push-bar reading “si prega di chiudere la porta’ (please close the door) legible next to the display cases labeled "Libya" and "Eritrea-Ethiopia" containing miscellaneous agriculture samples (Firenze, 2021); architectural axonometric of 'Villaggio Oliveti' in Tripolitania designed by Italian architect Florestano di Fausto, drawing in 'EDILIZIA RURALE: Urbanistica dei centri comunali e di borgate rurali' p.545 (D. Ortensi, 1941); Italian rural settlers waving aboard ship on way to Libya "Il viaggio dei rurali in Libia: allegria a bordo del 'Sardegna'" in 'ROMA' Napoli, 4 November 1939 (periodical room, Library of Congress); cover image of 'Cirenaica Pacificata' (R. Graziani, 1932); plan for 'roman encampment' or concentration camp as administered in Cirenaica, map in 'La Nuova Italia D'Oltremare' p.194 (A. Piccioli, 1933); Log53's 'Why Italy Now?' and contributing title "Under the Blue Mediterranean Sky" (M. Calvo-Platero, 2021); travels by train and sea (Lombardia e Puglia, 2021-2022)

In Fall 2021, Log—an independent journal on architecture and the contemporary city by Anyone Corporation—published Log53: Why Italy Now? The various contributions included journalist Mario Calvo-Platero's "Under the Blue Mediterranean Sky." As Anyone, Calvo-Platero narrated a vignette of Italian colonial architecture in Libya and praised the “multicultural” work of Italian architect Florestano di Fausto. After contextualizing the architectural works of Di Fausto, to whom we might ask Calvo Platero, was his architecture—in form or function—"multicultural?" Di Fausto's oeuvre spanned from urban to rural— the Arco dei Fileni marking the Roman crossroads between Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (1937), the Italian agricultural settlement of Villaggio Oliveti (1935-38), the Uaddan Hotel and Casino in Tripoli (1935), the Offices of the Istituto Nazionale Fascista per la Previdenza Sociale, INFPS (1938) in Libya; as well as the Padiglione della Libia in Mostra Triennale d’Oltremare (1940) in Napoli. His work—towards a “Mediterranean Vision" of colonial architecture—is exemplary in illuminating the ambiguous project of Modernization during Italian colonialism in Libya. This research presentation acts as a continuous conversation of my master's thesis (PoliMi, 2022) which partly examined cultural and historical geographer David Atkinson's analysis (2012) of Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben's concepts of "bare life" and "state of exception" (1998). Atkinson asserts how the concentration camps in Cyrenaica (1928-1933) strike a clear application to Agamben's theories on “state of exception.” The camps—spaces of “pacification” (Graziani, 1932) or places of genocide (Ahmida, 2020)— thus cannot be separated from the integral step toward the construction of the modernist landscape in the late 1930s. The spatial qualities of the agricultural villages for Italian mass settlement, like Villaggio Oliveti (Tripolitania) and Beda Littoria (Cyrenaica), illuminate how modern architecture was instrumental in building a civilized Modernità masking the “[spaces] of exception.” Nonetheless, Log53’s space for "Under the Blue Mediterranean Sky" elicits reasoning why the phenomena of “colonial amnesia” exists in the 'Now.'